Telling stories since the early 90’s …

When I’m not writing for clients, I write for myself.

I won’t share my childhood creations here — I wouldn’t put you through that.

But you can enjoy a little taste of what I make by scrolling down the page, or go over here to see a couple of personal essays.

I write fiction & non-fiction novels, children’s books, screenplays and short stories. All films are done with Aaron Ly, Director/DOP.

FILM & AUDIO

NON-FICTION BOOKS

how to kick ass at travel planning - non-fiction, 2019

The ultimate guide to planning the ultimate first big trip abroad, whether you’re 18, 28, or 80. Packed with step by step, detailed information and relatable stories, How To Kick Ass At Travel Planning is a companion to make the planning process easy, so you can get on and enjoy your trip.

It’s available in Kindle and paperback from Amazon.

travel pro - non-fiction/journal, 2019

The follow-up to How To Kick Ass At Travel Planning, Travel Pro is an on-the-road guide for travellers, with mixed pages of lined journal paper, dotted grid paper, and informative content to refer to on your journey such as common scams and illnesses, and how to deal with culture shock.

NON-FICTION SHORT FORM

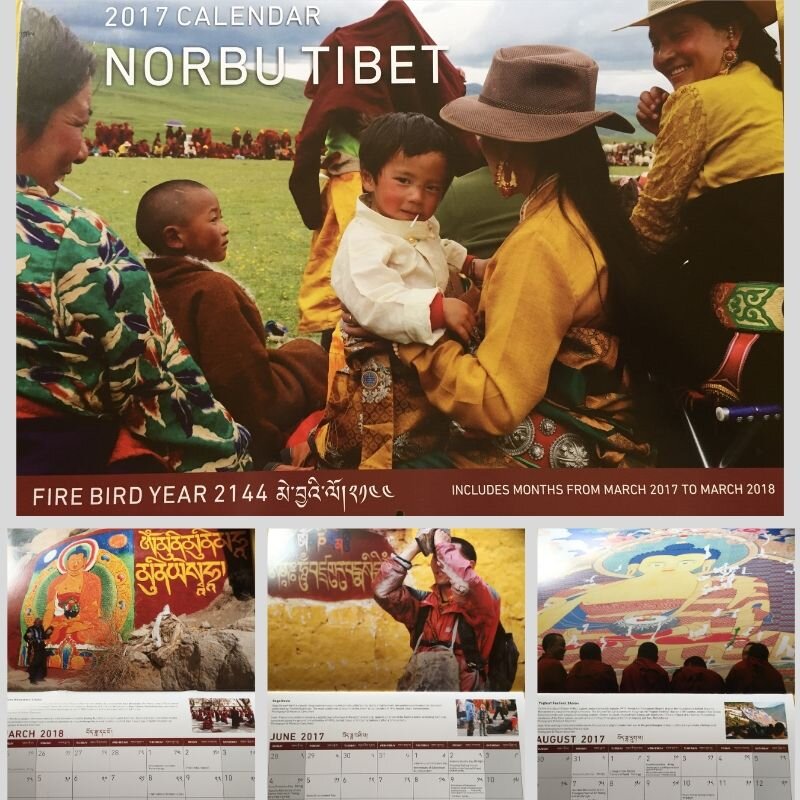

Norbu calendars - 2016-18

With business partner Robert Sherman, I helped create these Tibetan/Chinese/Gregorian calendars for Norbu Inc, a social enterprise, using our original photos and captions designed to educate and increase awareness of Tibetan culture.

EDUCATIONAL CHILDREN’S

The Tibetan adventure book - children’s book, 2014

An activity book full of puzzles and activities designed to educate and engage children with Tibetan culture, language, and locations. The book was hand-illustrated by me, and put into print by a local school in Lhasa.

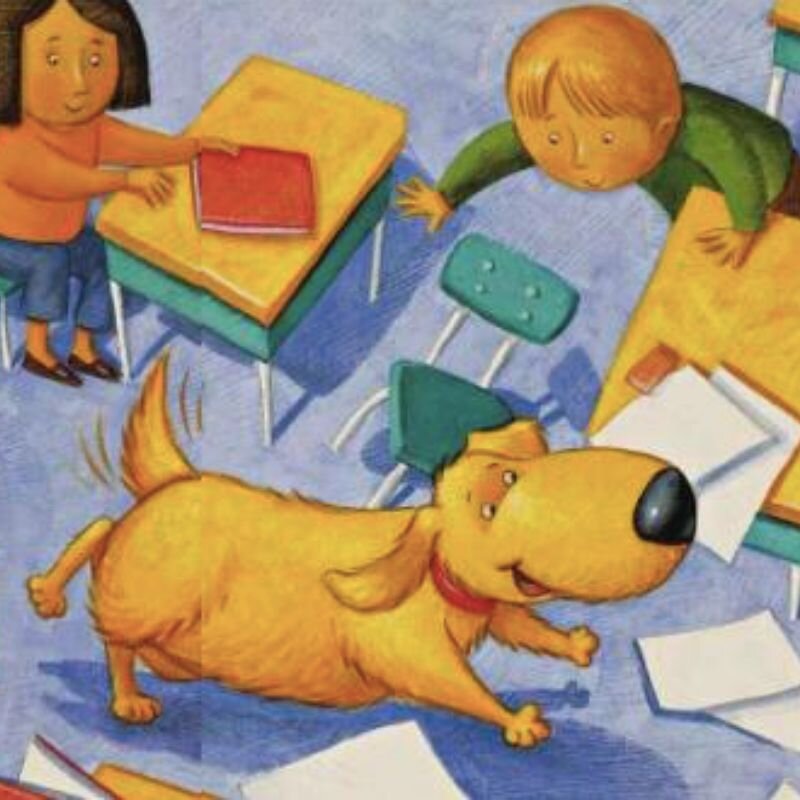

educational ESOL resources - 2017

While teaching drama in Chengdu, China, I was commissioned to write two short plays based on picture books for the level 1 & 2 classes. With limited vocabulary and a direction to rhyme, I created ‘Cool Dog, School Dog’, and ‘Flip the Dinosaur’.

FICTION

I currently have a novel and several short pieces of fiction in the works.

Links to come as pieces are published.

Photography

Click the left and right arrows to see the full gallery

Each year around March or April, the town of Bhaktapur in Kathmandu, Nepal, hosts its annual Bisket Jatra festival.

For days leading up to the opening of the week-long event, a chariot is constructed in the main square of the ancient city, piece by piece. At the close of the festival, the chariot is dismantled and stored carefully for another year.

Here, local boys play on the half-finished chariot in the days before the festival.

On the first day of Bisket Jatra, thousands of people crowd into Bhaktapur to see the chariot careen through the narrow streets, pulled by teams of local men.

It’s a spectacle for tourists and Nepali alike, who follow the chariot en masse from square to square over the course of a few hours.

The chariot’s journey begins at the uppermost square of Bhaktapur, and travels through narrow streets and alleyways downhill to the bottom square, propelled by a combination of gravity and manpower.

However, occasionally the chariot becomes stuck and its downhill momentum isn’t enough to keep it going. In these cases, teams of men on either side of it yank it from either end in turn until the large wheels begin rolling again and it carries on.

Here, the chariot conveniently lost its momentum halfway through a turn that would have sent it straight into a heritage building. The alleys and turns in ancient Bhaktapur are tight, and it’s not uncommon to see power lines yanked down or wooden decorative features swiped by the out-of-control chariot.

To send it down the right track, teams of men and volunteers from the crowd try to correct the chariot’s course by tugging on the trailing ropes.

While the young men strain and heave to turn the chariot, older onlookers and tourists quite happily stand back to enjoy the spectacle.

Controlling or correcting the chariot gives young men a great opportunity to test their strength, as if battling for a tug of war they’ll never win. Although some come away bruised and dirty, they’re safe from serious harm as long as they remain above the heavy chariot.

A local Newari man looks down from his window at the crowds chasing the chariot through the streets.

This young boy, proudly bearing the Nepali flag on his cheek, was closely minded by his older sister while they waited for the chariot to enter this final stage of its journey.

Spectators can easily be trampled or crushed below the chariot wheels if they are trapped in front of it. While many young men see it as an adrenalin rush - leaping to grab hold of it as it passes, or standing in front until the last minute in a game of chicken - not all of them come away successful.

After a painful negotiation through the final tight passages, the chariot emerges down the channel into the final square.

The men who’ve been pulling with all their might to encourage it to make the right turns will now have to leap clear or be struck by the dangerously careening chariot.

While two men stand joyously on the front prow of the Bisket Jatra chariot, others cling desperately to the bottom, knowing that if they let go they could be seriously injured.

The chariot is now moving at speed and increasing in pace as it follows a steady and open descent to the final square.

Deep within the remote mountains of western Sichuan Province, known to Tibetans as Kham, the monastic town of Yachen Gar is home to 10,000 nuns and monks from across Tibet and China.

Most arrive with nothing, and build their own ramshackle houses in a shantytown-like arrangement, using each others walls for support. Women far outnumber the men, who have only begun arriving in recent years and are confined to their own side of the river.

In 2016, Yachen Gar was relatively untouched by outsiders and unseen by the government. It’s residents were happy, friendly, and open.

Sadly, in 2019 Yachen Gar faced the same fate as it’s male-dominated counterpart Larung Gar. Police and armed personnel evicted 80% of the monastic town’s residents and began bulldozing their houses so they could not return. This is ongoing now.

Contrary to common western belief, nuns do not spend their entire day in meditation or peaceful rest. Much of their daily schedule is spent in class studying the sutra and tantra, learning to perform particular rites, studying philosophy, and - for many who never received an education at home - learning to read and write.

As in any school, there are those who study hard and complete the homework ahead of time, and those who leave it til the last minute. These nuns were memorising pages of scripture on their way to the assembly hall one afternoon, but whether they were getting ahead or falling behind I can’t say.

Due to the enormous number of nuns who have made Yachen Gar their home, they are divided into large classes who must share the different assembly halls on a rotating basis, each taking turns to gather and recite their twice-daily prayers.

Many nuns and monks alike are never without their prayer wheel in hand. Containing 100,000 repetitions of the mantra “Om Mani Padme Hum”, they believe that every rotation of the wheel is equivalent to speaking the mantra 100,000 times.

Over on the men’s side of the river, they also gather twice a day to recite their prayers, prayer wheels in hand.

It’s common for boys as young as seven to be sent to monasteries to become junior monks, although as this image shows they don’t always have the attention span required to make it through prayers.

In the old days, it was expected for Tibetan families to send at least one son to the monastery, and if he did well it was a source of pride for the family. These days, boys are encouraged to go to China instead for education.

While some younger monks struggle to remain focussed, others take to it naturally and even ask to join the monastery from a young age.

Tibetans explain this as being their karma - in a past life, they must have been very good and devout people, who are now blessed with strong faith, a smart mind, and steadfast devotion to the Buddha’s teachings.

These boys will attain much positive merit over their lifetime, becoming closer to enlightenment than the majority of their monk brothers.

Not all women in robes at Yachen Gar have been nuns their whole lives. Women aren’t encouraged to become nuns in the same way that men are to become monks, so many don’t choose this path until later.

Some women arrive pregnant, or with small children. Their histories differ - husbands who died, husbands who beat them, unplanned pregnancies - yet they are all received the same by the community here.

Their children accompany them until they are old enough to attend the nunnery nursery and primary school, where they will learn reading, writing, math, and a variety of other subjects.

In the nunnery primary school, the children are dressed in a mix of lay and monastic clothing, reflecting their different backgrounds.

Some are the children of nomads who live around the outskirts of Yachen Gar, there to provide the nuns with yak milk & butter. The nearest town is two mountain ranges away, too far for many to take their children.

Some children came to Yachen with their mother when she took the robes and became a nun. Some were even born here, and call it their home. These children dress like little Rinpoches in shining satin shirts and jackets, imitating the great teachers who lead the nuns in prayer.

Pilgrims from all over the region, and from as far afield as Lhasa and China, come to Yachen Gar to make offerings and receive blessings.

One of the main activities performed by pilgrims is to follow the looping trail of prayer wheels around the main assembly hall and mani pile, spinning each wheel as they go.

Similar to the handheld prayer wheels, these giant golden cylinders hold hundreds of thousands of printed mantra inside them, so that each rotation is as effective as speaking it that many times.

Around the outer perimeter of the monastic town is a trail, also lined sporadically by prayer wheels. This is called the kora, meaning “to go around”.

Walking a kora is an act of devotion and offering, but is also enjoyed as a social event by many who take the opportunity away from the crowds to giggle and gossip as they walk.

Others , meanwhile, use the opportunity to memorise their scriptures or practice recitations aloud.

In the evening, around the outer kora where the trail climbs the hill, these young monks and nuns were practicing a dance.

Although the men and women of Yachen Gar usually do not socialise together, this group appeared to be good friends and didn’t mind each other’s company.

The women sat on the grass, singing classic melodic tunes, while the men danced in the evening light, only occasionally realising how badly out of time they were.

The nearest town is two mountain ranges and an expansive plain away, yet here in the remote eastern plateau of Tibet a thriving nunnery of 10,000 has developed.

Gar literally means “camp”, which is how this now-epic institution began. Over the years as more people arrived, ramshackle buildings sprung up in disorganised clusters and roads were built through the middle.

These days the village has limited power and phone signal, but still lacks basic sanitary facilities and clean water, leaving it stuck between its old slum-like appearance and a modern liveable town.

In 2019 authorities began the destruction of Yachen Gar in the interest of public health and safety. It’s unknown what they will allow to remain.

Along one of the main streets, ramshackle houses lean against each other for support. Newly arriving nuns build with whatever materials and assistance they can find or afford.

Some nuns build small boxed on top of their houses, just big enough to sit upright cross-legged in, for private meditation purposes.

Personal space is not a luxury afforded to the nuns of Yachen Gar. Many share their shacks with one or two others, finding it cheaper and warmer to share resources, especially in winter.

While arrivals boomed at Yachen, infrastructure development fell behind.

Most of Yachen’s walkways and public areas remain muddy, or half-paved. The central artery through the houses is so far the only complete road-with-sidewalk paved street.

The exterior of a typical restaurant in Yachen Gar - made of the same makeshift material as the houses, and displaying the menu on a bi-lingual Tibetan and Chinese poster outside (with images for those who are illiterate).

The entire nunnery is vegetarian, an unusual move for Tibet where even senior monks eat yak meat on a regular basis. Here though, they believe that living a vegetarian life is an important way to practice compassion for living beings - an important tenet of Buddhism.

This little shack contains one of many convenience stores around the village. These are run by local laypeople to supply the nuns with their daily dose of snacks in the form of red bull, sprite, instant pot noodles, lollipops, and vegetarian fake meat.

Another small shop shack, this one supplies robes and clothing accessories for men and women in Yachen Gar.

Although the number of nuns in Yachen far outweighs the number of monks, both are catered for equally by this man’s shop.

At an intersection outside the main assembly hall, which is shared by monks and nuns on alternate days so they don’t interact, is a sign which reminds each which way they should go.

To the left, monks are directed toward the men’s living area of Yachen Gar. To the right, nuns are directed to the bridge that’ll take them across the river to their part of the village.

Around mid-morning, the nuns pour over the bridge from their houses across the river toward the main assembly hall, for the daily teaching led by their Rinpoche.

Nuns of all ages live at Yachen Gar, and attend the daily teachings and prayers. The women support each other as sisters, and playfulness is encouraged in the young.

This young woman was playing a game with her friend, pretending to hide behind her hat and not see her.

In spring 2018 I found myself accompanying a friend on an usual mission.

A lover of food and Tibet, Rob had recently founded a start-up to make yak meat jerky with the aim of cracking into the health foods market. He’d so far only needed small amounts of yak meat while perfecting the recipe and process, but was now looking to scale up production and needed a stable - and plentiful - source.

So with the help of a local friend, we found ourselves driving out of already-remote Hongyuan township to an even more remote countryside speckled with small farms and stupas. Here, we arrived at our destination for the morning.

Despite how commonly we refer to them as “yak”, these domesticated animals technically aren’t that.

They are known properly as “dzo”, which is a cross-breed of yak and cow, making them easier to manage domestically while retaining the benefits of yak hair, milk, and meat.

True yaks are much larger, with a bulkier frame, and are only male - the female of the species are known as dri.

One of the many developments brought by Chinese rule was permanent winter homes for nomads.

Throughout the winter months, when the ground is frozen and there’s little available pasture, families now have a permanent dwelling to return to. In Spring, when the grasses have grown again in the higher meadows, the family will pack up their tent and precious belongings into a truck and head back to the higher altitudes with their herd.

By far the most comfortable and versatile item of Tibetan clothing, the chupa (choo-pa) varies from region to region and can usually be a good indication of where a person is from, and what they do.

A nomadic chupa is characterised by elongated sleeves (which serve like gloves in the cold) and an oversized pouch in the front, useful for storing a day’s food when out on the mountain, or keeping small animals and children safe.

The wide, fertile winter pasture is sectioned off with invisible lines, agreed upon by each of the neighbouring families to ensure they all have good grass available for their herd, and no section suffers from over-grazing.

In the valleys and on the mountain slopes the only fences are those along roads - and sometimes not even there. Yaks are mainly left to roam free, but it is the responsibility of the herdsman to keep check of where they are, and bring back any stragglers with a quick rock from his slingshot.

Each day for nomads starts and ends with their yaks - sending them out to pasture, and bringing them back in.

Families living near each other share resources to take care of their herds through the day, with family members taking turns to spend the day out on the hills.

In Tibetan language, norbu means “precious”.

Given their usefulness to Tibetans, it’s no coincidence that the term for baby yak is nor.

Also, aren’t they just precious?

Back inside, breakfast is prepared from the Tibetan staples of tsampa and butter.

Tsampa, in the wooden box, is finely ground barley flour that for breakfast gets mixed with a knob of yak butter and hot black tea to form a dense and filling doughy ball.

A favoured drink of Tibetans (that disturbs many outsiders) is butter tea: black tea, boiled with a large chunk of yak butter and a dose of salt.

It’s rich and satisfying, filling like a soup, and has the added bonus of moisturising your chapped lips!

Got a creative project you’re working on?

I’d love to be involved!

Hit me up, let’s chat about what you need.